Bring Back the Whigs: A Modest Proposal for an Emotionally Regulated Republic

In an age of political furor, institutional decay, and king-sized egos, perhaps the only path to sanity is to revive the one party built on contradiction, caution, and the radical idea that Congress—not demagogues—should rule the day.

Summary: In this satirical and philosophical essay, Martina Moneke imagines “resurrecting” the 19th-century Whig Party as a model for today’s fractured American politics. She opens with a critique of the nation’s obsession with spectacle, personality cults, and moral grandstanding, presenting the Whigs as early anti-demagogues who valued restraint, institutional balance, and paradoxical thinking. Economically conservative yet socially progressive, champions of infrastructure and education yet wary of spectacle, the Whigs embodied tension and moral seriousness. Moneke envisions a modern Whig platform with Congressional mindfulness retreats, a national infrastructure corps, and a Bureau of Civic Virtue, emphasizing emotional self-regulation, civic discipline, and slow, steady governance. Reflecting on historical failures, including the party’s split over slavery, she draws parallels to contemporary crises such as climate denial, political polarization, and America’s ongoing struggle to confront its foundational harms.

Author: Martina Moneke

Author Bio: Martina Moneke writes about art, fashion, culture, and politics, drawing on history, philosophy, and science to illuminate ethics, civic responsibility, and the imagination. Her work has appeared in Common Dreams, Countercurrents, Eurasia Review, iEyeNews, Kosmos Journal, LA Progressive, Pressenza, Raw Story, Sri Lanka Guardian, Truthdig, and Znetwork, among others. In 2022, she received the Los Angeles Press Club’s First Place Award for Election Editorials at the 65th Annual Southern California Journalism Awards. She is based in Los Angeles and New York. Follow her on Substack.

Credit Line: This article is licensed by the author under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Date: February 13, 2026

SEO-optimized keywords: Bring Back the Whigs, American Whig Party, Martina Moneke, political satire, anti-demagogue politics, congressional governance, 19th-century politics, emotional self-regulation, infrastructure policy, civic discipline

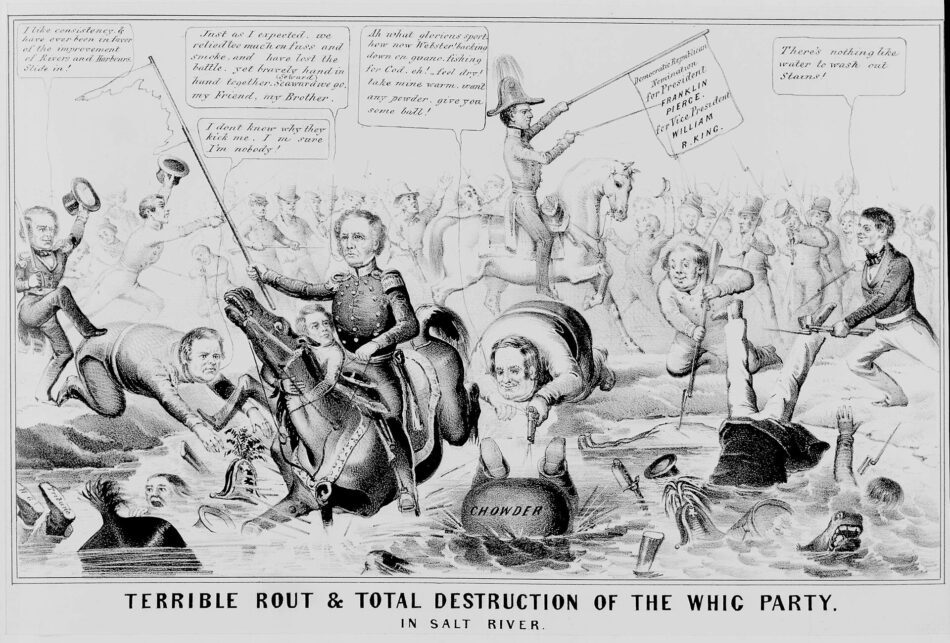

IMAGE: Terrible rout & total destruction of the Whig Party. In Salt River WIKIPEDIA COMMONS

“The people have entrusted the government to us; it is our duty to restrain our passions and govern for the good of all.” —Henry Clay, Whig leader

We have elected kings and prophets, pied pipers and moral grandstanders, each promising salvation while devouring the institutions meant to contain them. We have exhausted the future with our appetites. Perhaps it is time to resurrect the past—not for nostalgia’s sake, but because the 19th century has more wisdom to offer our shattered present than we care to admit. Let us bring back the Whigs.

The Whigs were not a party in the sense we understand parties today. They were an experiment in restraint, a wager on moderation, a belief that the passions of a single executive should never outweigh the deliberation of Congress. They were founded in opposition to Andrew Jackson, whom they mockingly called “King Andrew,” and in doing so became the first Americans to fear the very democracy they helped sustain. Jackson, a man of immense charisma and temperamental will, represented the dangerous allure of personality over principle. The Whigs, by contrast, believed governance should be tedious, predictable, and morally serious—a stance that seems almost radical in our age of constant spectacle.

But why the Whigs? Because contradiction is the native tongue of our nation. The party was a coalition of diverse and sometimes conflicting interests: northern industrialists, planters who enslaved people, western small farmers, Protestant reformers, and advocates for Native American rights. While unified in opposition to Jackson, these groups held vastly different ideologies on issues beyond executive power, making it difficult to establish a uniform national platform. At the same time, the Whigs balanced “conservative” values—prioritizing social stability and property rights—with a progressive vision for national improvement through a strong, active federal government. They championed infrastructure projects, a national bank, and protective measures—the “American System”—while paradoxically opposing federal overreach in other contexts. They prized restraint and moderation in both passion and public demeanor, believing emotional self-regulation essential to sustaining governance and civic life.

Their internal division over slavery ultimately destroyed the party, providing a cautionary tale for any polity that avoids its moral reckonings. This failure—split between conscience and convenience—is a lesson we have yet to learn. We cling to binaries, mistake rage for principle, and confuse spectacle with governance.

Imagine, then, a resurrected Whig Party. A party that values calm over political fury and believes Congress, not kings or demagogues, should govern. As the Whigs themselves observed, ambition must be tempered by principle, and principle must be served by moderation. A party that invests in roads, canals, and today’s renewable grids with the same reverence once reserved for the Erie Canal, infrastructure projects, and protective measures that fueled national growth—acts that bound a nation together and supported prosperity in ways no celebrity president ever could. A party that insists moral seriousness need not be performative, and that paradox is not a flaw but a mirror of human reality.

Let us imagine some modern Whig policies: a Congressional mindfulness retreat program to temper the passions of legislators; a national infrastructure corps focused not on monuments but on the quiet repair of bridges, grids, and educational systems; and a federal Bureau of Civic Virtue tasked with reminding citizens that politics is rarely entertainment and often boring—yet essential. Perhaps this corps would oversee a national climate-resilience initiative that links civic discipline to ecological survival, or coordinate programs to expand equitable public education and civic engagement. Such seemingly far-fetched proposals could be the antidote to the perpetual drama we now mistake for progress.

History reminds us that restraint is lonely work. The Whigs understood that governance requires boredom, delay, and compromise. They trusted the slow grind of Congress over the flash of the presidency. They championed policies—supporting industry, education, and infrastructure—not for glory, but because they bound a nation together and served the common good. In imagining their return, we are reminded that politics is the art of patience, and patience is no longer fashionable. And now, as we face ecological collapse, social inequity, and a society addicted to spectacle, those lessons resonate more urgently than ever.

We cannot bring them back in reality. Yet the lesson endures: if we cannot revive a party that embodied restraint, we can honor its memory by resisting the seduction of ragebait, performative politics, and moral pretense. Perhaps the Whigs, if they were alive today, would not solve our crises. But they would remind us that wisdom often comes slowly, uncelebrated, and unglamorously—and that a polity built on reflection rather than frenzy is a polity worth striving for.

Let us then propose that the Whigs return—not to glorify a bygone era, but to remind us of what governance might be if it were reflective, deliberate, and moral, not for show but in practice. In choosing the Whigs, we choose a party that does not flatter us but steadies us. In that steadiness, we might find the faintest echo of wisdom, and the faintest hope that we can survive ourselves.

We have lived for too long under the famous curse, “May you live in interesting times”—a curse we have embraced as a lifestyle. If interesting times have given us crises, demagogues, and institutions stretched to breaking, then maybe the only blessing left to ask for is the humblest one: May America be boring again.