The president who set the standard for scandals

Editor’s note: This is the twenty-ninth entry in the writer’s year-long project to read one book about each of the U.S. Presidents in the year prior to Election Day 2016. You can also follow Marcus’ progress at the @44in52 Twitter account and with this 44 in 52 Spreadsheet.

In America, presidential scandals are something of a national pastime. Even in 2016, when the two major presidential candidates both have scandals attached to their name, we rush to put it into historical context: how bad was it, really?

Not all political presidential scandals are created equal, after all. You’ve got your abuse of power, your cronyism, your cover-ups. Nixon’s Watergate isn’t the same as, say, the Whiskey Ring under Grant. But this kind of behavior runs right through the lineage of the office.

Sex scandals in the Oval Office aren’t anything new, either. The office of the presidency is littered with extra-marital affairs, from Sally Hemmings to Monica Lewinsky. Presidents and shenanigans go together like peanut butter and jelly.

Lucky for us, Warren G. Harding had all kinds of scandals to choose from — an impressive feat for a man who didn’t even complete his first term.

Harding, the eighth, and final, president to be born in Ohio, Harding is the beneficiary of a kind, revisionist biography from John Dean in this entry of The American Presidents series.

Yes, that John Dean — Nixon’s former White House counsel, Watergate co-conspirator, and the whistleblower who told Congress that Nixon had been secretly taping all his conversations. He knows a thing or two about scandalous presidents.

But here Dean digs deep to cast Harding in a positive light, claiming that Harding’s reputation has been sullied by a “distorted and false Harding history.”

Harding may not have been the worst president of all time — James Buchanan usually takes that dubious honor. But his short 882-day term has to rank in the bottom group, plagued by scandals both political and personal.

Most eyebrow-raising were the various women in Harding’s life. First was Carrie Phillips, with whom Harding had a 15-year affair, cutting it off in 1920 just as he was getting his campaign for president underway.

Proving that presidential sex scandals never go out of style, the release of Harding’s steamy love letters to and from Philips (which you can read here, you dirty rascal) created quite a stir when they were finally released by the Library of Congress in 2014.

Take this blush-worthy excerpt:

“Wouldn’t you like to get sopping wet out on Superior — not the lake — for the joy of fevered fondling and melting kisses? Wouldn’t you like to make the suspected occupant of the next room jealous of the joys he could not know, as we did in morning communion at Richmond?”

Also of note was his apparent relationship with Nan Britton, who published a book after Harding’s death called The President’s Daughter in which she alleged she had a relationship with Harding, that they romped in the White House itself, and that he fathered her daughter.

Dean goes out of his way to shoot down these claims, citing his own research of Britton’s papers. He made his own unsuccessful attempts to track down any potential descendants.

Dean’s book was published in 2004; 11 years later, DNA tests revealed that (cue Maury Povich) Harding was the father.

And then there was Harding’s wife, Florence. Before her relationship with Harding, Florence Kling had an affair that resulted in a child out of wedlock. The kid was raised by her father, with whom the Hardings had a tumultuous relationship.

Florence embraced the celebrity of being First Lady — and, as I would learn in the subsequent biography of Calvin Coolidge, was capable of holding deep grudges against those who wronged her.

But even more sensational is the long-standing rumor that Florence poisoned Harding as revenge for his adultery. Dean barely touches on the theory, which was largely based on the claims of the nefarious Gaston Means. But it lives on thanks to the internet, a fertile breeding ground for such conspiracies.

(Closer to the truth may be that the president’s personal doctor, a homeopath who had treated Florence, likely contributed to an ailing Harding’s death via misdiagnosis.)

Though buried by time and subsequent events, the Teapot Dome affair remains as one of the all-time worst presidential scandals, a sordid affair involving bribery and oil.

While Harding was never directly linked to the scandal — most of the blame fell on his Secretary of the Interior, the appropriately-named Albert Fall — its revelation while he was still alive did his health no favors.

The final rulings in the scandal came down years after Harding’s death in 1923. By then, the damage was done to Harding’s reputation. After all, it all went down on his watch.

These were hardly the only scandals of the Harding administration. There was Charles Forbes’ Veterans Bureau affair, a kickback scheme that set the tone for the bureau for decades to come. As a bonus, this tale includes the (possible apocryphal) story of Harding literally choking Forbes out of anger.

That John Dean would want to put a polish on Harding’s presidency is hardly surprising. Dean spun himself out of Watergate into success, cooperating with prosecutors and serving a reduced four-month sentence for a single charge of obstruction.

Subsequently, Dean became an investment banker and a writer. He penned a memoir of his time in the White House, Blind Ambition, which was later turned into a TV movie with Martin Sheen portraying Dean.

Dean makes one passing, winking mention of Watergate in his preface — noting that it surpassed Teapot Dome as “the most serious high-level government scandal of the 20th century” — but it never factors into the rest of the book.

While certainly revisionist, Dean’s account doesn’t come across as nearly as biased as, say, Unger’s Monroe bio. It’s an easy read and one that doesn’t let Harding completely off the hook (though Dean does dig up a few excuses).

Reading the biography of a scandal-plagued president as written by a member of the inner-circle of another scandal-plagued president is enjoyable enough, so long as you provide more than one grain of salt.

Days to read Washington: 16

Days to read Adams: 11

Days to read Jefferson: 10

Days to read Madison: 13

Days to read Monroe: 6

Days to read J. Q. Adams: 10

Days to read Jackson: 11

Days to read Van Buren: 9

Days to read Harrison: 6

Days to read Tyler: 3

Days to read Polk: 8

Days to read Taylor: 8

Days to read Fillmore: 14

Days to read Pierce: 1

Days to read Buchanan: 1

Days to read Lincoln: 12

Days to read Johnson: 8

Days to read Grant: 27

Days to read Hayes: 1

Days to read Garfield: 3

Days to read Arthur: 17

Days to hear Cleveland: 3

Days to read Harrison: 4

Days to read McKinley: 5

*Days to read T. Roosevelt: 15

*Days to read Taft: 13

*Days to read Wilson: 10

*Days to read Harding: 3

Days behind schedule: 4

IMAGES:

Warren G. Harding, a president whose administration would be haunted by scandals even after his death.

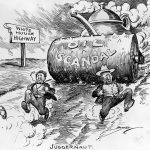

The juggernaut of scandal rolling towards the whitehouse after members of President Warren Harding’s government were implicated in an oil scandal.

IMAGE: CLIFFORD K BERRYMAN/MPI/GETTY IMAGES

Screenshots

For more on this story and video go to: http://mashable.com/2016/08/08/scandals-of-warren-harding/?utm_campaign=Feed%3A+Mashable+%28Mashable%29&utm_cid=Mash-Prod-RSS-Feedburner-All-Partial&utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed#ymUMMmuHNkqD